In 1926 Hiram Abrams was the managing director of United Artists, the company that had Rudolph Valentino under contract. On May 22, Valentino signed a new three-picture deal with John W. Considine, Jr. head of the producing unit which made the Valentino pictures; his next film, based on the life of Benvenuto Cellini, was already being developed. Also in May, Abrams made a publicity hire, Victor Mansfield Shapiro, to assist in the buildup to the release of Valentino’s next picture, The Son of the Sheik.

According to the U.S., College Student Lists, 1763-1924 at Ancestry.com, Shapiro graduated from New York University with a B.S. degree in 1913. The 1916 entry for New York University reveals that after graduation, Shapiro worked for The New Yorker in the art-editorial areas and as a cartoonist and Advertising Manager for a publication named Violet.

The information included in the student list was apparently collected before Shapiro’s next career move. By 1916, Shapiro was working for V-L-S-E, Incorporated. V-L-S-E was a partnership between four film distribution companies–Vitagraph, Lubin, Selig, and Essanay–which had been formed in 1915, with Albert Smith named as president.

We know this because Shapiro was among those who participated in the formation of the Associated Motion Picture Advertisers. Prominent members during the first year of the Associated Motion Picture Advertisers (AMPA) in 1916 included men who would later be involved with Rudolph Valentino: Executive Board members Jesse Lasky of the Photoplay Company and Harry Reichenbach of the Frohman Amusement Company. Included in the list of general members was “V. Mansfield Shapiro , V.S.L.E.”

Source:

August 5, 1916

Page 12

But just after AMPA was formed, there were changes involving the V-L-S-E organization. According to Wikipedia, a “proposed a merger of the distribution companies Paramount Pictures and V-L-S-E with Famous Players Film Company and Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company, … was foiled by Adolph Zukor. When Vitagraph purchased a controlling interest in Lubin, Selig, and Essanay. V-S-L-E was dissolved on August 17, 1916, V-L-S-E head Albert Smith finally sold the remaining part of the company to Warner Brothers on April 20, 1925. (See Note 1 below for an interesting reference to Smith’s autobiography in which he refers to hiring a 17-year-old Rudolph Valentino.)

We don’t know exactly when Victor Mansfield Shapiro became an independent publicity man, but by 1926 he was a big enough player in the business to be hired by Hiram Abrams to devise a publicity campaign to help boost Valentino’s appeal; his last film, The Eagle, had received good reviews but yield only modest returns at the box office. Valentino needed “a hit” because his star power was perceived as being on the wane as Ramon Navarro and John Gilbert gained popularity. (See the headline below.) Previews of The Son of the Sheik in Santa Monica and Burbank went well and on July 9 the Los Angeles premiere filled Grauman’s Million Dollar Theatre to capacity with one of the largest and most brilliant gathering of film stars at the time. The reaction pleased both the studio and Valentino and it looked like they were on the way to the hit they wanted.

Valentino left his home for what would be his last time to start his publicity tour, arriving on July 15 at his first stop in San Francisco for a press event, where he met Mayor “Sunny” Jim Rolph before heading to Chicago en route to New York. Still complaining of stomach pains which had plagued him since February when he was shooting The Son of the Sheik, he carried a large supply of sodium bicarbonate with him on the train. (His brother Alberto had departed California the day before with his wife and son Jean, also heading to New York where they would depart on July 24 for the return trip to Italy.)

Just before Valentino arrived in Chicago for a layover of a few hours before connecting with the train to New York, the editorial “Pink Powder Puffs” appeared on Page 10 of The Chicago Tribune on Sunday, July 18, 1926. With that editorial, Shapiro saw the opening he needed to power his publicity campaign.

Valentino had already been the target of innuendo, racist comments and mockery well before this piece was published. As early as 1922, Photoplay‘s Dick Dorgan called Valentino a “bum Arab” and invoked the term “wop” in a satire of The Sheik; a few months later, in the July edition which featured Valentino on the cover, Dorgan produced the “Song of Hate.” Valentino was so angered that he demanded that the studio bar Dorgan from the studio lot.

The “Pink Powder Puff” editorial that appeared in The Chicago Tribune on Sunday, July 18, 1926 (Page 10)

“…Better a rule by masculine women than by effeminate men.”

When The Los Angeles Times reprinted the editorial, it added an earlier, even more caustic editorial (the Five-Yard McCarty piece) that had been published on November 19, 1925, as well as an “exclusive” report about the reaction delivered by Valentino when he arrived in New York on July 20. At the same time the cartoon by Harry Haenigsen which appeared in The New York Evening World on July 21 clearly expressed the view that a boxing match would become a major public relations event even though Valentino insisted his challenge was “real” and “not for the purpose of publicity.”

Reprint in the Los Angeles Times (July 21, 1926) with the earlier “Five-Yard McCarty” piece published in November 1925, alongside a story about the “challenge” letter in response

(Scroll down to see the original draft of the “challenge” letter)

“Isn’t Life Complicated?” Cartoon

The New York Evening World, July 21, 1926, Page 16

Note the depiction of Valentino at the top left of the cartoon

…Needing a “hit”… New York Daily News, Sunday, January 4, 1925

Note, by contrast, the article about the Barthelmess household which ran next to the story about Valentino’s waning drawing power. His previous film, The Eagle, while well-reviewed, had only been a modest box office success.

Note the opening salvo…the reference to the “fresh gardenia a London-tailored lapel.”

Also note that Valentino stated that he was an American citizen, which was not true; he had only filed a Declaration of Intent in November 1925.

The Associated Press interview conducted in New York on July 20 added more color to the “Exclusive” carried by the Los Angeles Times:

"I'm mad," Valentino rasped out to reporters. "I'll make whoever wrote that foul stuff look like a full moon. This is no publicity stunt. I'm really mad. I can't understand how the editor of the Chicago Tribune let that editorial get into the paper." "I'm am not angered by the reference to my being the son of a gardener. What made me mad is the whole tone of the insulting thing. In Italy in the absence of the name of the writer of an article the editor may be challenged. I regret that system is not in vogue here." (AP story as printed in the Waco-News Tribune, [Waco, Texas] Wednesday, July 21, 1926, Page 5)

Before the Shapiro papers came to light, Alan Elllenberger quoted a press agent named Oscar Doob in The Valentino Mystique who claimed that “he was the one who suggested that Valentino challenge the “Pink Powder Puffs” editorial writer to a duel” and that he “needed a publicity stunt because we were getting ready to open one of his latest pictures” (Page 17) (See Note 2). And Simon Constable, in a blog piece describing the incident, speculates that Valentino’s business manager George Ullman actually was the one who “stirred things up” and goes so far to wonder if Ullman could have protected Valentino more if he hadn’t shown him the newspaper that day.

However, material uncovered by Giorgio Bertellini brings a new perspective to the whole incident. Bertellini is Professor/Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Film, Television, and Media at the University of Michigan. His latest work, entitled The Divo and the Duce: Promoting Film Stardom and Political Leadership in 1920’s America,… “won the 2019 American Association of Italian Studies book award, for the category ‘Film/Media.'”

And it is the archival material belonging to Victor Mansfield Shapiro that Bertellini has examined which sheds new light on what may have transpired during the latter half of July 1926. (The description of the contents of the archive is below.)

The entire work is available at JSTOR, a site that “provides access to more than 12 million academic journal articles, books, and primary sources in 75 disciplines.” The direct link to the book is here. Of particular interest is Chapter 6 entitled Stunts and Plebiscites (Pages 145-162). Also, quite by accident, I found that anyone with a Kindle can download the entire book for free.

(I originally had embedded the PDF available at JSTOR into this post but decided to clarify the Terms and Conditions with JSTOR and was advised that doing so would breach their terms…so, I need to take a different route, which follows below.)

A short summary of the ground covered by Bertellini was included in a review in The Sydney Morning Herald, which to date is the only discussion of the book and the Valentino-related information that I have found in the general press. The article entitled Macho men: The links between Valentino and Mussolini by Desmond O’Grady was published on June 14, 2019.

[The image]the Italian-born Valentino also was distorted. Bertellini illustrates this with a discovery about the 1926 Pink Powder Puff scandal in Chicago. The Chicago Tribune published an anonymous editorial lamenting Valentino’s encouragement of the installation of powder puffs in men’s toilets. Valentino responded indignantly to this slur and offered to prove his virility by boxing a bigger and more athletic man "Buck" O’Neal. Valentino knocked him out. (Editor's Note: the correct spelling is "O'Neil".)

Bertellini has found proof that it was all a publicity stunt arranged by a PR man, Victor Shapiro, because Valentino’s sequel to his most successful film, The Sheik, had not aroused much interest in Chicago. The fake scandal changed that.

The following section presents the key points revealed by the Shapiro material as discussed in The Divo and the Duce.

- Shapiro already had a major career as an independent publicity man and had actually met Valentino on the set of The Eagle in 1925. He became UA’s publicity man for Valentino and it seems he may have ghostwritten a number of Valentino’s articles near the end of his life. “Shapiro at first expressed the sort of conventional thinking that emerged out of brainstorming sessions in UA’s Publicity and Still Photography Departments. The sessions centered on ‘how to make Rudolph Valentino more acceptable to men customers.'” The usual tactics would involve photos of Valentino sparring with Jack Dempsey, riding horses, polo with Douglas Fairbanks, or perhaps photographing him as female reporters were invited to watch Valentino engaging in exercise while “nude from the waist up.” This was the “play the Sheik card” strategy and would carry the tagline “Men, why be jealous of Rudy Valentino? You, too, can make love like he does. See ‘Son of the Sheik.'” But there were doubts that this approach would make enough of a splash to “revive Valentino’s career” (Page 149).

- Shapiro followed the conventional approach, sending profiles which emphasized Valentino as “sensual with animal grace,” photographs, etc. to the press, first-run theaters, and picture outlets but this “only caused a ripple with the males.” “Shapiro recounted how the “Pink Powder Puff” editorial fell outside the scope of conventional thinking and achieved the ultimate goal of any publicity campaign: ‘get the opening'” (Page 150).

- Shapiro’s transcripts reveal that his boss Abrams had started negotiations for the distribution of The Son of the Sheik with the largest theater chain in Chicago, Balaban and Katz. They rejected his offer of exhibition rights, and wanted to lower the price, claiming that “Valentino didn’t mean a thing in Chicago.” This is what set things in motion, as Abrams asked Shapiro to created a “publicity campaign unmatched in [Valentino’s] career” (Page 150).

- On July 10, Shapiro said he was instructed by Abrams to send “the livest wire” on his staff “to do something about Valentino” when he stopped in Chicago between trains. Jimmy Ashcroft* was the pick; he was told to leave New York and get to Chicago and get “‘something on the front page, something–anything, provocative and entertaining.”‘ Shapiro met on July 12 as Ashcroft left for Chicago to give final instructions; both were on the same page (Page 150). (*Elsewhere referred to as “John” Ashcroft.)

The “opening” came when The Chicago Tribune published the “Pink Powder Puff” editorial on Sunday, July 18, 1926. Shapiro spotted it, as he called it, as a potential “Valentine to Valentino.” Valentino arrived in Chicago on July 19. Ashcroft showed him the piece (which Shapiro designates as “A”) and began “stoking up [his] indignation.” Then, Ashcroft gave a prepared reply (referred to as “B”) to William Randolph Hearst’s Chicago Herald-Examiner, The Chicago Tribune‘s arch competitor. Within hours, Hearst had the prepared reply over the newswires and his papers across the country. The speed of the response further encouraged other editorial managers around the country to take the “Pink Powder Puff” piece seriously even though some recent academic analysis suggests the piece was really an ironic tone, not to be taken literally (Page 150) and was simply written in the typically sarcastic style of the day.

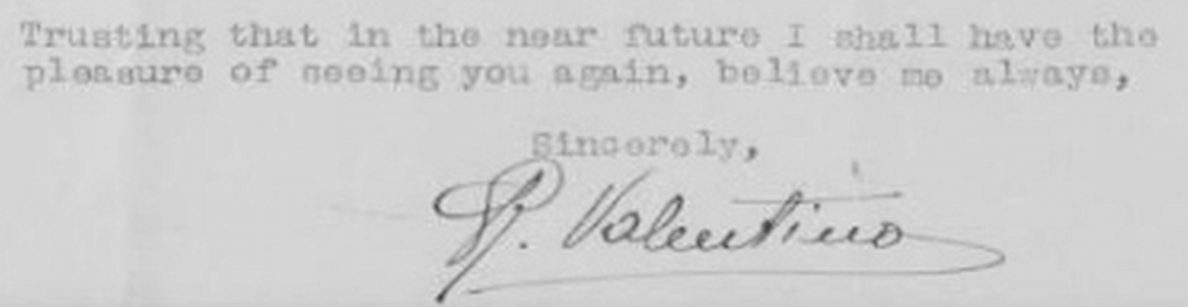

The response/”challenge” letter signed by Valentino (described as “B” by Shapiro)…

Note the misspelling of the word “defy” as “defi” in two places.

Note the scribbled addition to the third paragraph…which bears no likeness to the handwriting of Valentino as seen in original letters.

The note reads:

“Didn’t know who you are or how big you are but this challenge stands if you are as big as Jack Dempsey.”

Source: Worthpoint.com auction lot

- Shapiro then instructed Ashcroft to “keep [Valentino] fired up” on the way to New York as Ashcroft and Shapiro and his assistant, Warren Knowland were pulling together what to do next before Valentino and Ashcroft arrived in New York (Page 150-151).

Give him some printable catch lines, have him carry a copy of the novel Cellini, his next picture. We'll have photos at the station, a press conference at the hotel, with Prohibition's best handing out copies of, of Chicago editorial and Rudy's answer. Then it's up to ye gods, and ye gods it was (laughter).

- Shapiro contacted his friend Lloyd “Red” Stratton of the Associated Press on the morning of July 20, told him where Valentino would be staying and “suggested” the AP would have first access, although not exclusive access, to Valentino. Everything was ready in advance. The welcome would include a police escort for Valentino from Grand Central Station to the Ambassador Hotel. (George Ullman would recall that “the sight of motorcycle traffic officers clearing the way for his triumphal car always thrilled him” (The S. George Ullman Memoir, Page 215). At the station, the crowd needed to be controlled, with the station guards managing to get Valentino into his car without having his clothes ripped off. Shapiro finally met George Ullman and they discussed who would be handling what: Shapiro would handle the “picture end” of the publicity, while Ullman would stick to the “personal matters.” However, according to Shapiro, in reality, he was handling everything. (This included his idea that “‘Rudy was to receive the press in his blue and green silk robe and purple pajama, for the benefit of the lady reporters [laughter].'”)

- By that afternoon the Associated Press and the Hearst papers were carrying the story and from that point on, the phones rang non-stop with requests for interviews–“every news outlet in town, fan and general magazines, foreign press, film critics, males and females, sport writers” called and they all received personal interviews. More than 100 members of the media filed in and out of Valentino’s suite (Page 151).

Bertellini goes on to relate Shapiro’s descriptions of the staged match between Valentino and Frank “Buck” O’Neil on the hotel rooftop in front of a Pathe’ cameraman, which the author describes “as the promotional equivalent, as a staged event, of Valentino’s prepared response to the press.” Satirical cartoons, like the one pictured above, considered the “challenge” to fight an anonymous editorial writer as nothing other than a stunt. But, it was an effective stunt, because Shapiro received a report from Ashcroft in Chicago that the papers were breaking stories about how “‘the Balaban and Katz crowd never, never again would say Valentino doesn’t mean a thing there.'” Ashcroft also told Shapiro that when Valentino returned to Chicago for The Son of the Sheik‘s premiere, another statement (referred to as “C” by Shapiro) to the anonymous author of the Pink Powder Puff editorial would be ready.

The premiere of The Son of the Sheik at the Strand in New York was greeted with “mobs of spectators,” long lines and big ticket sales; a few days later the scene would be repeated at the premiere in Chicago. Valentino arrived at the train station to an enthusiastic crowd and shouted, “Mr. Editor, I am here. I am ready. Where are you?” He posed with flexed muscles and boxed with a welterweight named “Kid” Hogan at a gym in the Loop (Leider, Dark Lover, Page 375). Valentino’s second prepared statement ( “C” ) in which Valentino stated that he felt “vindicated” was issued and went national in a few hours.

"The heroic silence of the writer who chose to attack me with any provocation in The Chicago Tribune leaves no doubt as to the total absence of manliness in his whole makeup. I feel that I have been vindicated."

When Valentino went back East and appeared in Atlantic City on August 3rd, the crowds were there, too, and after his appearance at that premiere, he went to the Gus Edwards revue. There, where Valentino would dance his last tango, he was given a pair of boxing gloves just in case he got a chance to use them on the author of the “powder puffs” editorial. When The Son of the Sheik opened in Brooklyn a few days later the crowds came out again to fill the theater. Bertellini relates how Shapiro thought the entire effort was “‘the most extensive and intensive publicity break in Rudy’s short life,”‘ described himself and Valentino as “‘more than passable actors”…and recalled that Valentino “‘was acting his resentment'” (Pages 151 and 153).

Shapiro’s remarks seem to be a true recollection of the situation, namely, that Valentino willingly participated in the scheme. In the context of his stressful physical condition as well as the pressure of needing The Son of the Sheik to be a hit to not only enhance his career but also to help relieve his worrying financial predicament (large debts), Valentino played his role to the hilt, not only in print, but in speaking with reporters. In the “challenge” letter shown above and in the subsequent interview in the Los Angeles Times report, he made a point of saying that this was “not for the purpose of publicity” which sounds disingenuous. While claiming that he had written the letter, he told the Associated Press in New York on July 20 “…I handed it to my publicity agent and let him do the rest.” And Ellenberger writes that “Valentino later alluded to the act that someone else may have suggested or at least helped with the challenge when, in Chicago ten days later, he said: ‘I’m not boasting about my physical strength. I never should have allowed my press agent to make such a point of fact'” (The Valentino Mystique, Page 17).

But, was he really “[acting] his resentment” as Shapiro states? Shapiro wasn’t an intimate of Valentino, so he most likely didn’t have the deepest insight into Valentino’s emotional states. His job was to churn out publicity. There is very little doubt that Valentino did find the editorial insulting and that it took a toll on him. Unfortunately, Valentino’s words and actions provided a field day for the cartoonists and writers who scented blood and ratcheted up the pressure. (I’ve found a number of articles from papers all over the country whose tone mocked his statements and dress, even as they delivered the facts of the story.) Valentino had become a running joke.

Valentino was genuinely disturbed by what he felt was as an assault on his image as a man as well as the racist overtones of the piece. The “slave bracelet” became a point of contention regarding Valentino’s “manliness.” His manager George Ullman recounts how as they were traveling from Chicago to New York after the anonymous editorial was published, Valentino’s “whole being was disorganized” and that the words “stuck in Rudy’s craw….Rudy repeated the words more times than I heard him utter any other phrase in all the years I knew him” (The S. George Ullman Memoir, Page 78).

After nearly two weeks of publicity generated by the “Pink Powder Puffs” editorial and with only one more scheduled appearance in Philadelphia, Valentino was free to enjoy himself…and he did with a whirlwind of socializing at New York City venues, attending shows, and visiting Long Island’s Pleasure Island on weekends to escape the city heat. One weekend he went out to Long Island with his old friend George Raft; Raft recalled that “He looked pretty bad and …as we pulled up to to this fabulous home he told me ‘…It’s all been great, but I am a lonely man'” (George Raft, Lewis Yablonsky, Page 43). He took up with showgirl Marian Benda, while dealing with Pola Negri who was left behind working in Los Angeles. He mended fences with his first wife Jean Acker, Adolph Zukor and his old friend June Mathis. He discussed his next film project based on the life of the Benvenuto Cellini with his future co-star Estelle Taylor, the wife of his friend Jack Dempsey, four days before he was stricken.

He indulged in excessive drinking and eating and taking copious amounts of sodium bicarbonate for what he called his “nervous indigestion.” Adela Rogers St. Johns, also staying at the Ambassador Hotel in New York, recalls how just before being stricken with his fatal illness, he rummaged through her bathroom medicine cabinet in search of sodium bicarbonate after indulging in a heavy lunch of snails and told her how the fling with Pola wasn’t real, bemoaning how “Pola always drives me to the bicarbonate of soda.” And, he was still not over his divorce, telling St. Johns that “In the courts, she divorces me. Can you divorce in the heart?” (Love, Laughter and Tears: My Hollywood Story, Pages 177-178).

Even though he felt “vindicated” and was indulging in non-stop partying, Valentino remained preoccupied with anguish over the Pink Powder Puffs smear and the effects of the publicity campaign. About a week to ten days before he was stricken, Valentino sought a meeting with H. L. Mencken, the famous critic and essayist. Mencken, who wrote for The Baltimore Sun, was known as the “Sage of Baltimore” and described the meeting after Valentino died.

...So he sought counsel from the neutral, aloof and aged. Unluckily, I could only name the disease, and confess frankly that there was no remedy...He should have passed over the give of he Chicago journalist, I suggested, with a lofty snort--perhaps, better still, with a counter gibe He should have kept away from the reporters in New York. But now, alas, the mischief was done. He was both insulted and ridiculous, but there was nothing to do about it. I advised him to let the dreadful farce foll along to exhaustion. He protested that it was infamous...Sentimental or not, I confess that the predicament of poor Valentino touched me. It provided grist for my mill, but I couldn't quite enjoy it...Here was one who had wealth and fame. And here was one who was very unhappy (Prejudices, Sixth Series, Pages 308,311).

(“Prejudices” is available at Archive.org. The short, poignant film “Goodnight Valentino” which depicts the meeting is available here.)

In the April 15, 1922 issue of Pantomime magazine, Valentino was the subject of a column entitled “Read ‘Em and Know ‘Em“– “A ‘Mental’ Photograph of Rodolfo Valentino“. Asked what his favorite motto was, he replied “Live and Let Live!” When the slave bracelet that his then wife Natacha Rambova gave him started garnering attention, George Ullman noted that Valentino ignored “their jibes and insults” (The S. George Ullman Memoir, Page 117). Luther Mahoney, who became Valentino’s handyman, also stated that Valentino “never paid any attention to such comments from such people. He was not used to making bad remarks about people so they just rolled off him, like water off a duck’s back” (The Intimate Life of Rudolph Valentino, Page 71). But the Pink Powder Puffs attack was harder to deal with that July. As Adela Rogers St. Johns commented “Although all of us, Herb Howe, Jimmy Quirk, me bugged him to, Valentino couldn’t let it alone….It was the last straw, somehow” (Love, Laughter and Tears, Page 176).

Valentino was rushed to the Polyclinic Hospital on Sunday, August 15. When he awoke after surgery from the ether his first words were “Did I behave like a pink powder puff or like a man?”

Victor Mansfield Shapiro was still on the job when, although out of town, when he first read the newspapers reports of Valentino’s hospitalization on August 16. According to his recollections, “‘I didn’t believe it. Nonsense!’ So he called his assistant, Knowland, fearing that Knowland had been ‘pulling a stunt without [his] knowledge'” (Bertellini, Page 153).

Although Shapiro, Ullman and UA hoped it would quickly pass, in the meantime they saw it as another publicity opportunity. Shapiro and Knowland went to the "press room at the hospital" and even though Ullman was in charge of "personal publicity," the crisis called again for a breach of contractual protocol: "Biographies and pictures of Valentino were passed out by Knowland."...He died on August 23, 1926, to the apparent surprise of everyone--his fans, the studio, and his publicists. The latter group was to react to it in ways that would frame both his passing and afterlife. (Bertellini, Pages 153-154)

…and that reaction would be seen in a funeral, unlike any funeral 1920’s New York had ever seen before…

NOTES

NOTE 1: “Founder Albert E. Smith, in collaboration with coauthor Phil A. Koury, wrote an autobiography, Two Reels and a Crank, in 1952.[16] It includes a very detailed history of Vitagraph and a lengthy list of people who had been in the Vitagraph Family. In the text of the book he also refers to hiring a 17-year-old Rudolph Valentino into the set-decorating department, but within a week he was being used by directors as an extra in foreign parts, mainly as a Russian Cossack.” –Wikipedia

NOTE 2: Ellenberger also states that the studio and Valentino’s manager George Ullman would hire “forty press agents to handle and publicize the funeral” to keep Valentino’s name in the public eye (page 62).

The Victor Mansfield Shapiro Archive

Title: Victor Mansfield Shapiro Papers , Date (inclusive): 1915-1967 Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: Victor Mansfield Shapiro was a independent publicity man for the Hollywood film industry. The collection consists of public relations and promotional materials relating to the motion picture industry, including questionnaires, codes, biographies, scrapbooks, clippings, photographs, and tapes of interviews with transcripts.

Box 4

7. Harry L. Reichenbach – greatest movie press agent

8. Experiences publicizing Rudolph Valentino

SOURCES

Bertellini, Giorgio. The Divo and the Duce: Promoting Film Stardom and Political Leadership in 1920s America. 1st ed., vol. 1, University of California Press, 2019. JSTOR

Ellenberger, Allan R. The Valentino Mystique: The Death and Afterlife of the Silent Film Idol. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2005.

Editors of Fourth Estate: A Weekly Newspaper for Publishers, Advertisers, Advertising Agents and Allied Interests. United States: Fourth Estate Publishing Company, 1916.

Leider, Emily W. Dark Lover: The LIfe and Death of Rudolph Valentino. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.

Mencken, H. L. Prejudices, Sixth Series. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1927. (Available for free download at Archive.org.)

Scagnetti, Jack. The Intimate Life of Rudolph Valentino. Middle Village, New York: Jonathan David Publishers, Inc., 1975.

St. Johns, Adela Rogers. Love, Laughter and Tears: My Hollywood Story. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1978.

Ullman, George. The S. George Ullman Memoir: The Real Rudolph Valentino By the Man Who Knew Him Best. Torino, Italy: Viale Industria Publicazionio, 2014.

Yablonsky, Lewis. George Raft. New York: A Signet Book, New American Library, 1974.

Wikipedia entry: Vitagraph Studios, redirected from V-L-S-E, Incorporated.